Photo Credit: Ann Brokelman

Their plentiful populations are indicators of ecosystem health, but they face numerous threats in urban and rural areas. This ranges from vehicle strikes and collisions with reflective glass windows (a common risk along their migratory paths), to pesticide exposure and habitat loss.

Kestrels have adapted well to surviving with the increase of human infrastructure, but some can end up sick, injured or orphaned because of the urban challenges they face. When that happens, Toronto Wildlife Centre (TWC) can help. The registered charity has dedicated the last 31 years to the rescue and rehabilitation of sick, injured and orphaned wild animals, and to educating the public on wildlife-related issues. With an accredited and fully-equipped veterinary hospital and rescue program, more than 120,000 wild animals from 300 species have been rushed in for urgent care – including American kestrels.

David was at work on a former landfill one day, when he spotted what appeared to be a bird struggling to fly. The poor animal wasn’t far from a station he was monitoring that burned off methane gas released from the decaying waste. When David approached what he could now see was a small falcon, he noticed her wings looked ragged and sparse – she couldn’t fly! Fearing the bird had been burned by the station’s flare, he knew she needed medical help.

The American Kestrel when she arrived at the Toronto Wildlife Centre

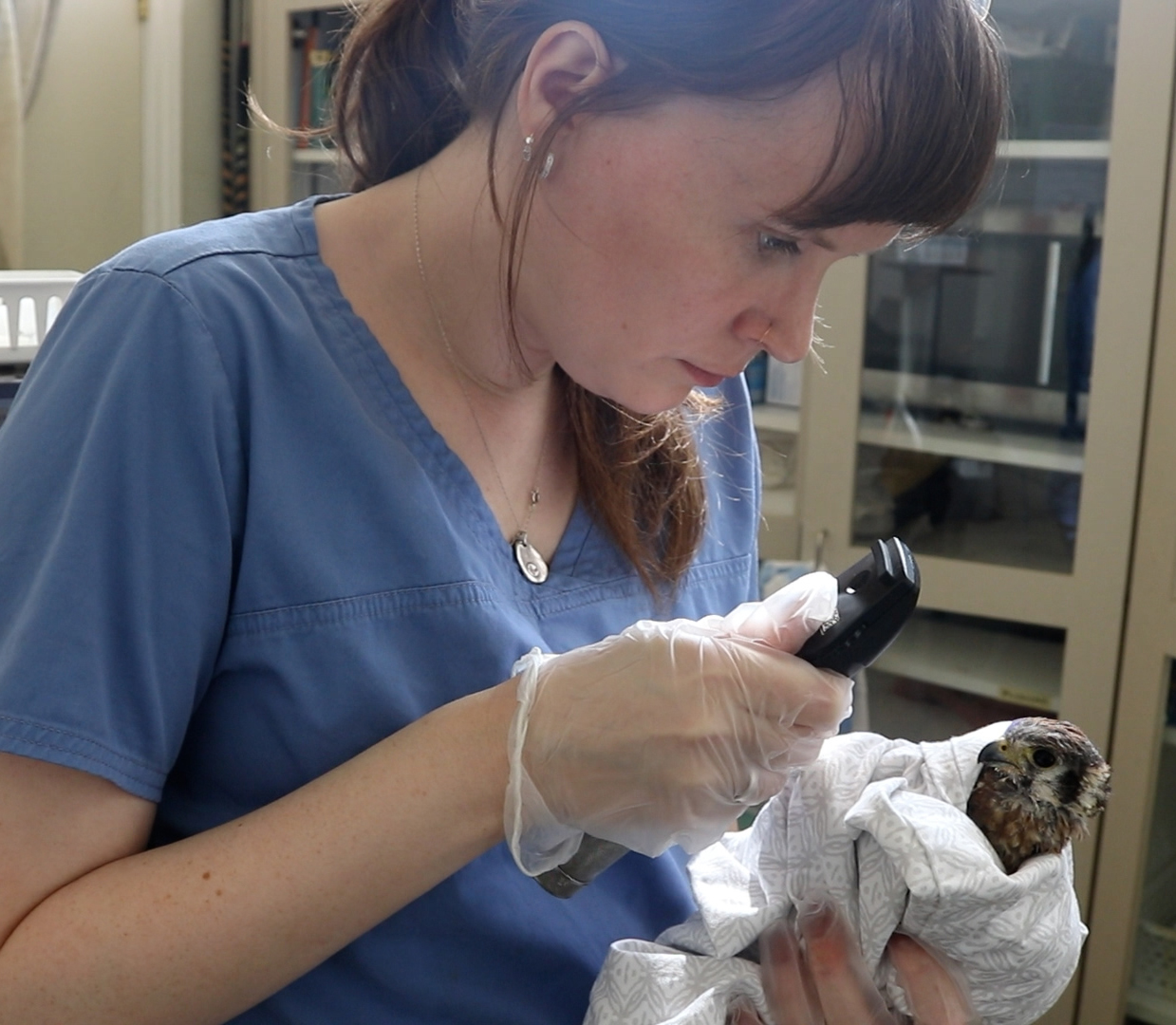

At TWC, each kestrel is meticulously assessed and diagnosed – from broken wings to head trauma to eye injuries – and the appropriate treatment is provided for the best chance of recovery. These energetic falcons are extremely high-stress, and being in an unfamiliar environment with humans is terrifying for them. In the wildlife world, extreme stress can be fatal, so TWC’s team does everything they can to keep them calm as they carry out their emergency care.

Working quickly and quietly, experienced Wildlife Rehabilitator Louise closely examined the new patient, taking note that most of the bird’s feathers were singed. She made sure to keep the animal’s head and eyes covered with a sheet to lower her stress levels. Besides the inability to fly in this state, the kestrel wouldn’t be able to thermoregulate with this much feather damage. Thankfully though, she had only sustained minor burns from the station flare. Louise gave the weak and dehydrated patient fluids and carefully placed her in oxygen caging to help increase her strength.

After a check with the Veterinary Team confirmed the falcon was otherwise in good health, she moved the patient to the intensive care unit to rest. Louise and her team closely monitored the kestrel daily, and fed her a diet of mice and a variety of worms and larvae, which mimicked her natural diet in the wild (kestrels primarily feed on insects/worms, small rodents, birds, amphibians, and reptiles). She hungrily gobbled up each meal, which was a great sign!

American Kestrel vet exam at Toronto Wildlife Centre, TWC

After showing improvement with a few days of treatment – often vocalizing loudly in protest during her checks, and flapping her sparsely feathered wings – the Rehabilitation Team set the kestrel up in a larger enclosure. Husbandry for falcons is an important part of their recovery, ensuring their environment meets their needs. They provided her with multiple perches that were appropriate for the size of her feet, and she perched comfortably upon them. Unlike bird of prey patients who can fly, hers was set closer to the ground so she could easily hop up onto them.

The kestrel was recovering well, but since this species molts only once per year she would need to undergo a process called imping to allow her to fly again sooner. This involves manually implanting new feathers in the place of damaged or missing feathers, giving her the ability to fly and reducing her time in captivity. Despite our medical team’s best efforts, some bird patients succumb to illness or severe injury and tragically don’t make it. But their wing and tail feathers are saved and stored, to be given to others of their species who need it most.

American Kestrel in care at Toronto Wildlife Centre’s ICU

When the time comes, after a successful imping procedure and days spent strengthening her flight in a vast outdoor aviary, she will be released to join her fellow kestrels who will have returned after their spring migration.

You may be wondering…why are American Kestrel populations currently in a state of decline when other raptor populations are stable?

In 2007, at the second symposia on the species held by the Raptor Research Foundation (RRF) in Fogelsville, Pennsylvania, there were alarming reports of Kestrel decline from across North America. Since then, numerous articles have been published on this issue, most notably authored by David M. Bird from McGill University in Montreal and John A. Smallwood of Montclair State University in New Jersey. Many people will recall the devastating impact organochlorines like the insecticide DDT had on raptor populations, but since banning the use of DDT in the 1970s, most affected raptor populations, such as Bald Eagles and Peregrine Falcons, have rebounded and stabilised. The fascinating question is why are American Kestrel population trends locked on this downward trend that has them headed for threatened or endangered status? This past summer, Catrin Einhorn of the New York Times brought the issue from ornithological circles into the mainstream when she wrote an article on the puzzling decline of the American Kestrel. Clearly, this is an issue that people care about.

Feathers for imping (not American Kestrel), photo courtesy of Toronto Wildlife Centre

Community scientists in the birding community will be proud to know that data on American Kestrel populations is captured through Christmas Bird Counts, Breeding Bird Surveys, autumn hawk migration counts, and nestbox monitoring. Here in Canada, there is not as much nestbox monitoring as there is in the U.S., which prompted my friend Stewart McLellan to start the Southern Ontario American Kestrel study four years ago. It is a nestbox monitoring program here in, as the name suggests, Southern Ontario. There are currently four of us researchers, Bill Read, Reiny Packull, Stewart McLellan and myself, participating with boxes located in Durham Region, Waterloo Region and Bruce County.

American Kestrel eggs in nest box, photo courtesy of Carly Davenport

In Ontario, we get to enjoy the company of Kestrels when some of the population migrates north to Canada to breed. Some of the North American population will remain in the U.S. year-round. American Kestrels are cavity nesters and prefer open grassland habitats, making them highly adapted to the hayfields and pastureland of rural Southern Ontario. Kestrels are primarily insectivores, although their diet is variable depending on their geographical location because they are generalists. The species readily takes to man-made nestboxes, which we are able to use under scientific permits to monitor and band the young for our research. The leading hypotheses on Kestrel decline are complex and probably deserving of more in-depth discussion, but I will do my best to summarise. First, there is the Cooper’s hawk hypothesis.

American Kestrels recently hatched in their nest box, photo courtesy of Carly Davenport

This is not the direct predation of the larger accipiter on the smaller falcon, but rather a greater abundance of Cooper’s hawks could be reducing the amount of breeding and foraging habitat available to the Kestrel, in turn reducing their abundance. Another hypothesis is habitat loss or habitat fragmentation, and this is certainly supported when we think of the overall decline of grassland birds in North America. Factors like urban sprawl and modern farming practices with monoculture cash cropping could be greatly reducing American Kestrel distribution and, therefore, their abundance. There has also been much debate on how insect decline impacts American Kestrels, but this hypothesis is incredibly nuanced, and no firm conclusions have been drawn in the literature to date. The use of pesticides and other industrial chemicals has been called into question but, again, difficult to interpret given the broad scale of American Kestrel decline. However, ongoing research into the impact of neo-neonicotinoids and rodenticides may hold some answers. And finally, to round out the hypotheses, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention climate change, the enemy of biodiversity writ large on a global scale.

Through the Southern Ontario American Kestrel study, we aim to document their breeding success, monitor local populations, and, through banding, determine where exactly they are overwintering. Part of the habitat loss hypothesis I have not yet mentioned is that little is known about wintering habitats. Through banding, we can obtain observations on their migration routes and from their wintering grounds. The banding data will greatly advance our understanding of whether wintering habitat loss, which we have considerably less research on, contributes to population decline.

Enjoy your observations of the American Kestrel this summer, and if you see any with blue bands bearing an two-letter alpha code, please report to the United States Geological Survey, Bird Banding Laboratory at https://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/BBL/bblretrv/index.cfm or call 1-800-327-2263.

American Kestrel Banding, Photo Courtesy of Carly Davenport

About the Authors:

Brittany Seki, As the Communications Manager for Toronto Wildlife Centre (TWC), Brittany Seki has spent almost 7 years establishing and growing TWC’s Communications Department, along with developing and executing strategic communication plans across diverse channels. With a Master’s degree and background in journalism, Brittany has leveraged her expertise in storytelling, digital media and content creation to orchestrate impactful campaigns that raise awareness, mobilize support, and drive action to help sick, injured and orphaned wildlife.

Carly Davenport, Carly is a clinical research trainee studying neurodegenerative disease in Dr. Carmela Tartaglia’s lab at the University of Toronto. Her scientific curiosity intersects with her love for the natural world and concern over the biodiversity crises we are all currently living through. She is committed to applying her expertise to better understand species decline in Southern Ontario and to reduce colonial human impacts on wildlife.